Of all the materials that have shaped the artistic imagination of China, none carries the philosophical weight of jade. Revered for over seven millennia — longer than porcelain, longer than silk, longer than bronze — jade has served as a vessel for the deepest aspirations of Chinese civilisation: purity, moral integrity, and the aspiration toward immortality. Among the many forms that jade carving has assumed, the white nephrite rhyton libation cup adorned with sinuous chilong dragons, and the auspicious figure of the mandarin duck, represent two of the most accomplished expressions of the carver's art — one invoking the archaic grandeur of ritual antiquity, the other embodying the tender symbolism of conjugal devotion.

The Stone of Heaven: White Nephrite and Its Place in Chinese Culture

The jade prized throughout Chinese history is nephrite — a dense, fibrous calcium-magnesium silicate with a hardness of 6 to 6.5 on the Mohs scale, exceeding that of steel. Unlike the brilliant green jadeite from Burma, which did not enter China in significant quantities until the eighteenth century, nephrite has been the material of Chinese jade culture since the Neolithic period. Its colours range from grey-green through celadon to the most treasured variety of all: the pure, luminous white known poetically as "mutton-fat jade" (yangzhi yu, 羊脂玉).

The principal historical source for this finest white nephrite was the river valleys around Khotan (Hetian) in present-day Xinjiang, where jade was gathered in the form of water-worn boulders from riverbeds — a method of collection that ensured the material had been naturally tested for flaws. When China gained direct control of these Central Asian jade-yielding regions between approximately 1760 and 1820, during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, an unprecedented quantity of fine nephrite flowed eastward to the imperial workshops in Beijing and the private ateliers of Suzhou, fuelling a golden age of jade carving.

The cultural significance of jade in China cannot be overstated. Confucius identified eleven virtues embodied by jade, including benevolence (in its lustre), wisdom (in its translucence), and integrity (in its hardness). To wear or handle jade was to participate in a material philosophy of moral cultivation. The ancient proverb junzi wu gu yu bu qu yu (君子無故玉不去身) — "The gentleman never parts from his jade without reason" — attests to the intimate, almost corporeal relationship between the stone and its owner.

The Rhyton Libation Cup: Archaic Form, Imperial Craftsmanship

The rhyton — a vessel in the form of a horn or animal head, designed so that liquid could be poured or drunk from the open end — has an ancestry that extends far beyond China, embracing the ceremonial drinking vessels of ancient Persia, Greece, and the Central Asian steppe. In the Chinese jade tradition, however, the rhyton libation cup (gongbei, 觥杯) assumed a character entirely its own: an archaistic form that consciously invoked the bronze ritual vessels of the Shang and Zhou dynasties while demonstrating the jade carver's supreme mastery of his medium.

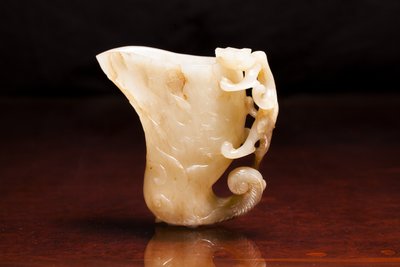

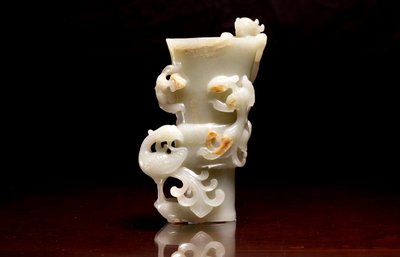

The most distinguished examples are carved from a single block of white nephrite and feature chilong dragons — hornless, sinuous creatures that belong to the dragon family but are distinguished by their youthful, serpentine form — clambering up the sides of the cup or coiling around its rim. The chilong motif first appeared on Chinese jade as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and became a staple of archaistic jade carving during the Ming and Qing periods, when antiquarian taste exerted a powerful influence on the decorative arts.

The carving of a rhyton cup demands exceptional skill. The hollow vessel must be worked both inside and out, requiring the carver to maintain precise control of wall thickness while simultaneously executing the relief decoration on the exterior. The chilong — often depicted in multiple, their bodies intertwined in compositions of dynamic complexity — are carved in high relief and sometimes pierced, their sinuous forms seeming to emerge organically from the surface of the stone. On the finest examples, individual scales are articulated, whiskers flow with calligraphic precision, and the expressions of the creatures convey a lively, almost animate quality.

The base of the rhyton typically terminates in the form of an animal head or a swirling cloud motif, recalling the shape of archaic bronze vessels. This deliberate evocation of antiquity was central to the object's purpose: the rhyton was not merely a functional vessel but a statement of its owner's learning and taste, a physical embodiment of the Confucian reverence for the wisdom of the ancients.

The Technique: Patience as Prerequisite

Jade carving is, in essence, an art of abrasion. The hardness of nephrite means that it cannot be cut or chiselled in the manner of marble or wood; it must instead be worn away using an abrasive compound — traditionally a paste of crushed quartz or garnet mixed with water — applied via rotating tools. During the Qing Dynasty, jade carvers employed iron rotary machines powered by a foot pedal, to which drills, diamond-tipped points, and leather polishing wheels could be attached in succession.

The process was extraordinarily labour-intensive. A single intricate piece could occupy a master carver for months or even years. The Qianlong Emperor, himself an avid connoisseur and poet on the subject of jade, was acutely aware of this investment of human effort. Under his patronage, the imperial workshops in the Forbidden City — and the renowned jade ateliers of Suzhou — produced works of technical virtuosity that scholars have described as the absolute peak of the ancient Chinese jade carving tradition. This same imperial atelier system that elevated carved cinnabar lacquer and other decorative arts also produced the finest jade carvings of the era.

The finishing stages were no less demanding. After the form had been roughed out and the relief decoration executed, the surface was brought to a high polish using progressively finer abrasives and leather buffing wheels. The resulting finish — smooth, warm, and faintly translucent — is one of the defining sensory qualities of fine jade. Jade is cool to the touch but warms rapidly in the hand, a property that has been celebrated in Chinese literature as a metaphor for the responsiveness of virtue to human contact.

Mandarin Ducks and the Language of Auspicious Symbolism

If the rhyton cup speaks to antiquarian scholarship, the carved jade mandarin duck (yuanyang, 鴛鴦) inhabits the warmer territory of domestic felicity. In Chinese culture, the mandarin duck is the preeminent symbol of conjugal love and fidelity, for these birds are understood to mate for life and are never seen alone. A pair of mandarin ducks, rendered in jade, constituted one of the most eloquent wedding gifts in the Chinese tradition — a wish for lifelong harmony between husband and wife.

Jade carvers rendered mandarin ducks with a naturalism that reflected the Qing Dynasty's taste for lifelike animal sculpture. The birds are typically depicted in paired compositions, their plumage rendered in meticulous detail, heads turned in attitudes of tender attentiveness. In the finest examples, the carver exploited the natural variations in the jade — subtle shifts from white to pale celadon, or the russet suffusions that occur naturally in certain nephrite boulders — to suggest the colouring of feathers, a technique that demonstrated both artistic sensitivity and material economy.

Beyond the mandarin duck, the repertoire of auspicious jade figures is vast. Bats signify happiness (the Chinese word for bat, fu 蝠, is a homophone of fu 福, "good fortune"); peaches invoke longevity; fish represent abundance (another homophonic pun: yu 鱼, "fish," and yu 余, "surplus"). Lingzhi mushrooms, associated in Daoist tradition with the elixir of immortality, appear frequently on jade carvings of the scholar's desk — brush rests, water droppers, and toggle pieces — where they served simultaneously as functional objects and embodiments of the owner's aspirations.

Connoisseurship: Reading White Jade

The evaluation of white jade carvings requires the cultivation of both eye and hand. The stone itself is the first consideration: the finest mutton-fat jade possesses a warm, even white tone with a subtle translucency and a surface lustre that has been compared to the sheen of congealed fat — rich, smooth, and faintly luminous. Stones that are chalky, opaque, or excessively veined are less highly regarded, though natural russet or honey-toned suffusions, when skilfully incorporated into the design, can enhance rather than diminish a piece's value.

The quality of the carving is assessed in terms of both technical execution and artistic conception. On rhyton cups, the depth and crispness of the relief, the fluidity of the chilong forms, and the thinness and evenness of the vessel walls are critical indicators. The interior of the cup should be smoothly finished — a detail that later or lesser copies frequently neglect. The polish should be even and warm, without the glassy, mechanical sheen that characterises modern machine finishing.

Dating jade carvings presents particular challenges. For this reason, provenance assumes exceptional importance. Pieces with documented histories — whether through published collections, exhibition records, or the inventories of distinguished dealers — command a significant premium.

The fitted hardwood stands (zuotuo) that traditionally accompany fine jade carvings are themselves objects of connoisseurship. Carved to follow the contours of the jade they support, these stands were typically fashioned from zitan (purple sandalwood) or huanghuali (yellow rosewood) and represent the Chinese reverence for complementary materials — the warmth of the wood against the coolness of the stone, the organic grain against the mineral purity.

Jadeite: The Burmese Stone and the Lotus Leaf Brush Washer

While nephrite dominated Chinese jade culture for millennia, the eighteenth century witnessed the arrival of a remarkable new material: jadeite (feicui, 翡翠), imported from the mines of Upper Burma. Jadeite is a sodium-aluminium silicate, mineralogically distinct from nephrite, and prized for its vivid colours — particularly the brilliant emerald green known as "imperial jade" (diyu, 帝玉). The mottled apple-green variety, with its subtle variations of colour and translucency, became a favoured material for scholar's desk objects, ornaments, and vessels during the nineteenth century.

The jadeite lotus leaf brush washer (bichong, 筆沖) presented here exemplifies the naturalistic carving tradition that flourished during the Qing Dynasty. Fashioned in the form of a curling lotus leaf, the vessel's triangular form follows the natural contours of the plant, with carved dragonflies, a frog, and lotus buds adorning its surface. The mottled green stone, with areas of deeper emerald and paler celadon, has been chosen and oriented to suggest the natural colouring of a living leaf — a technique that demonstrates the carver's sensitivity to the inherent qualities of the material. The matching carved hardwood lotus stand completes the composition, elevating the object into a miniature sculpture of the lotus pond.

Nephrite Animal Carvings: Symbols in Stone

Among the most appealing categories of Chinese jade carving are the small animal figures — hand-held pieces that served simultaneously as objects of contemplation, auspicious talismans, and tactile pleasures. The group of nephrite jade carved animals from the Qing Dynasty (eighteenth to nineteenth century) illustrates the range and vitality of this tradition. Carved from white and pale celadon nephrite with natural russet suffusions, these compact figures of mythical and real animals display the rounded, polished forms that invited handling and the gradual development of a warm patina through contact with the skin — a quality the Chinese call baojiang (包漿).

Each animal carries symbolic weight. The recumbent beast with ruyi-shaped tail may represent a qilin or bixie — auspicious mythical creatures that ward off evil and invite good fortune. The russet-skinned elephant invokes the homophonic pun between xiang (象, elephant) and xiang (祥, auspiciousness). These are not merely decorative objects but embodiments of wishes — for prosperity, longevity, and protection — rendered in the most enduring of materials.

The two finely carved nephrite pieces — a crane holding peaches and a group of birds on a branch — belong to the seventeenth to eighteenth century tradition of auspicious jade carving at its most refined. The crane (he, 鶴) is the bird of immortality in Chinese culture, associated with the Daoist sages and the Islands of the Blessed. Combined with peaches (tao, 桃) — the fruit of longevity — the composition forms the auspicious rebus heshou (鶴壽, "crane longevity"), a wish for a long and blessed life. The birds on a branch, carved with delicate openwork, demonstrate the piercing technique (loukong, 鏤空) that represents one of the supreme tests of the jade carver's skill, requiring the removal of material from within the composition without fracturing the surrounding stone.

An Enduring Legacy

White jade carvings occupy a unique position in the hierarchy of Chinese art. Unlike porcelain, which was produced in quantity at centralised kilns, or painting, which exists in two dimensions, jade carving is an art of individual confrontation between the carver and the stone — a dialogue between human intention and material resistance that can last months or years. Each finished piece bears the imprint of this encounter: the carver's response to the particular qualities of the stone, to its colour, its inclusions, its faults and virtues.

It is this quality of sustained, intimate engagement that gives jade its peculiar power. To hold a fine rhyton cup or jade mandarin duck — to feel the stone warm in the palm, to trace with the fingertip the sinuous curve of a chilong dragon's spine — is to participate, however distantly, in a tradition of material reverence that connects the present moment to the deepest past of Chinese civilisation.