Empress Dowager Cixi and the Art of Imperial Patronage

In the long chronicle of Chinese imperial porcelain, few commissions carry as much personal and political significance as the wares bearing the Dayazhai (大雅齋) mark. Produced at the Jingdezhen kilns during the waning decades of the Qing Dynasty, these famille rose porcelains — decorated with peonies, peaches, and birds against vibrantly coloured grounds — represent the singular vision of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), the most powerful woman in late imperial China. They are at once objects of aesthetic refinement and instruments of political self-fashioning, produced at a moment when the very survival of the dynasty hung in the balance.

The story of Dayazhai porcelain begins not in the kiln but in the garden. In 1873, during the twelfth year of the Tongzhi reign, work commenced on the restoration of the Yuanmingyuan — the great Garden of Perfect Brightness that had been devastated by Anglo-French forces in 1860. Within this vast complex, Cixi envisioned a personal residence: a suite of rooms designated Tiandi Yijia Chun (天地一家春), "The Whole World Celebrating as One Family in Spring," a name that had been bestowed upon the young Cixi by the Xianfeng Emperor himself decades earlier.

The furnishing of these private quarters required porcelain of a quality and character befitting the most powerful figure at court. The new-style porcelains bearing the Dayazhai mark were produced primarily during the first two years of the succeeding Guangxu reign (1875–1908), when Cixi had assumed regency following the untimely death of her son, the Tongzhi Emperor. By the second year of Guangxu, an extraordinary 4,922 porcelain pieces had been produced bearing both the Dayazhai and Tiandi Yijia Chun marks — a number that attests both to the scale of the commission and to the ambition of its patron.

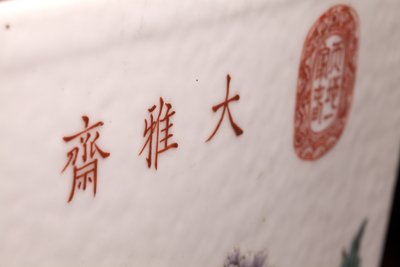

Genuine Dayazhai wares are distinguished by a system of three marks that, taken together, constitute what might be understood as Cixi's personal imperial insignia — an assertion of authority all the more remarkable for the fact that, as a woman, she could not formally adopt a reign mark (nianhao) of her own.

The first mark, rendered in iron-red enamel on the exterior of the vessel, reads Dayazhai — "The Studio of the Greater Odes," or, as some scholars have translated it, "The Studio of Utmost Grace." This hallmark, typically written horizontally, identifies the porcelain as part of the Cixi commission.

The second mark, also in iron-red, appears nearby within a small oval cartouche framed by two sinuous dragons. It reads Tiandi Yijia Chun — "The Whole World Celebrating as One Family in Spring" — the name of Cixi's personal quarters and, by extension, of the world she sought to create within them.

The third mark, on the base, reads Yongqing Changchun (永慶長春) — "Eternal Prosperity and Enduring Spring." This four-character inscription completed the triad, grounding the vessel in wishes for perpetual felicity.

The presence of all three marks in their correct positions — the Dayazhai hallmark and Tiandi Yijia Chun seal on the exterior, the Yongqing Changchun mark on the base — is essential to the identification of genuine pieces. Later copies, particularly those produced during the Republic period, frequently omit one or more marks, render them in incorrect positions, or display calligraphic inconsistencies that betray their later manufacture.

The decorative programme of Dayazhai porcelain is as distinctive as its marking system. The designs, which scholars have long associated with Cixi's own artistic direction, employ the mogu (没骨) or "boneless" painting technique — a method in which forms are rendered directly in washes of colour without the preliminary ink outlines that characterise most Chinese decorative painting. This approach, borrowed from the literati painting tradition, lends Dayazhai decoration a soft, painterly quality that distinguishes it from other late Qing imperial wares.

The primary motifs are drawn from the traditional repertoire of auspicious flora and fauna. Peonies — the "king of flowers" and symbol of wealth, honour, and feminine beauty — appear in luxuriant profusion, their petals rendered in shades of pink, white, and crimson. Peaches, the fruit of immortality in Daoist tradition, invoke wishes for long life. Birds, often depicted perched upon flowering branches, include magpies (harbingers of joy) and other species whose names form auspicious homophones in Chinese.

These motifs were executed against grounds of varying colour, each associated with a particular design scheme. The five principal designs are understood to represent the four seasons plus an additional spring variant, suggesting that a complete second set may have been contemplated but never fully produced. The ground colours include yellow (imperial), turquoise, aubergine, and pale blue, with the design remaining essentially consistent across variations. The yellow-ground examples, given the colour's exclusive association with imperial authority, are considered the most prestigious.

The Dayazhai commission represents something unprecedented in the history of Chinese imperial porcelain. Throughout the preceding reigns of the Qing Dynasty, the commissioning of imperial porcelain had been an exclusively male prerogative — an expression of the Emperor's personal taste and, by extension, of his legitimate rule. Cixi's appropriation of this privilege constituted a deliberate act of political self-assertion.

The cheerful, brightly coloured designs — at odds with the restraint that characterised earlier imperial taste — radiated the confidence of a patron who had navigated the treacherous currents of court politics for decades. That the commission coincided with the Tongzhi Emperor's assumption of personal rule, which should have marked Cixi's retirement from active governance, lends the porcelain an additional layer of meaning. In furnishing her retreat with wares bearing her own marks, Cixi was simultaneously preparing for a life of cultivated leisure and signalling her continued presence at the centre of power.

The tragic irony is that the Tongzhi Emperor died shortly after the commission was completed, before the Yuanmingyuan restoration could be finished. Cixi never occupied the rooms for which the Dayazhai porcelains were intended. She instead returned to active regency, ruling through the Guangxu Emperor until her death in 1908 — three days after the Emperor himself died under circumstances that remain the subject of historical debate.

The rarity and historical significance of Dayazhai porcelain have made it among the most sought-after categories of late Qing imperial ware. Genuine pieces from the original commission are exceptionally scarce; the 4,922 pieces recorded as produced have been dispersed across museums, private collections, and — during the upheavals of the twentieth century — into the wider market.

When assessing a purported Dayazhai piece, the collector should attend closely to the quality of the enamelling, the precision of the marks, and the overall condition of the ground colour. The boneless painting technique should exhibit a confident fluidity, with colour gradations that suggest a master painter's hand rather than the mechanical repetition of a workshop copyist. The iron-red of the marks should be consistent in tone and application, and the calligraphy should display the particular characteristics documented in published examples from the Palace Museum, Beijing.

Pieces produced during the Guangxu period as later copies of the original designs — sometimes bearing six-character Guangxu reign marks in iron red rather than the Dayazhai mark system — are of considerable interest in their own right, though they command lower prices than the original commission pieces. Republic-period copies, while often competent, generally lack the finesse of the imperial originals and may display reversed characters in the Tiandi Yijia Chun cartouche, the result of "mirror image" production techniques common in that era.

The Chinese Heritage has offered fine Chinese antiques, including Dayazhai famille rose porcelain from the Guangxu period, since 1978. Visit our gallery at Lucky Plaza, Orchard Road, Singapore.