The Art of Blown Cobalt in the Qing Dynasty

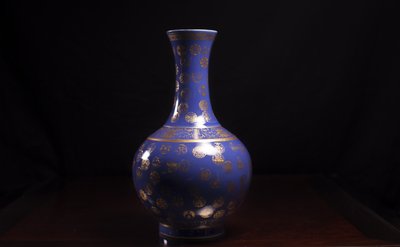

Few techniques in the long history of Chinese ceramics capture the interplay of control and chance quite like powder blue. Known in Chinese as chuiqing (吹青) — literally "blown blue" — this distinctive glaze emerged at the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen during the Kangxi reign (1662–1722) and remains among the most immediately recognisable achievements of Qing Dynasty porcelain production. When enriched with gilt decoration depicting Shou (壽) longevity characters and auspicious medallions, these wares represent a remarkable convergence of technical virtuosity and symbolic meaning.

The powder blue technique has its roots in a Ming Dynasty predecessor. During the Xuande period (1425–1435), imperial potters at Jingdezhen developed a glaze they termed salan (灑藍), or "sprinkled blue," which produced a mottled cobalt surface of considerable beauty. Only a handful of genuine Xuande examples survive today, making them objects of extraordinary rarity.

It was not until the reign of the Kangxi Emperor — widely regarded as a golden age for Chinese porcelain — that potters at the re-established imperial kilns perfected and refined this technique into what we now know as powder blue. The Kangxi Emperor had appointed Zang Yingxuan as director of the imperial kilns in 1682, inaugurating a period of exceptional technical advancement. Under Zang's supervision, artisans mastered a remarkable range of monochrome glazes, of which powder blue stands among the most distinctive.

What distinguishes powder blue from other cobalt glazes is its method of application. Rather than painting cobalt onto the porcelain body with a brush — the standard approach for blue-and-white wares — the potter blew finely powdered cobalt oxide through a bamboo tube fitted with a piece of gauze stretched over one end. This process produced a surface of remarkable subtlety: a deep, finely mottled blue that appears uniform from a distance but reveals, upon close inspection, a delicate stippled texture — an almost pointillist effect that no brush could replicate.

The gauze served as a sieve, breaking the stream of cobalt into minute particles that settled onto the unfired porcelain body in an even yet organically irregular pattern. The vessel was then coated with a transparent glaze and fired at high temperature, fusing the cobalt speckles into the body and producing the distinctive soufflé effect that collectors prize. This technique demanded considerable skill: too heavy a hand produced a flat, lifeless ground; too light, an uneven and patchy surface.

Powder blue porcelain was frequently enhanced with gilt decoration applied over the fired glaze. The most prized examples bear Shou (壽) longevity characters — the Chinese ideograph for long life — rendered in gold against the luminous cobalt ground. These characters often appear within circular medallions, their rounded form echoing the cyclical nature of time and the Daoist pursuit of immortality.

The gilt was applied using finely ground gold mixed with a binding medium, then fixed in a second, lower-temperature firing. This technique, while producing effects of considerable splendour, was inherently fragile. The gold sat upon the surface of the glaze rather than within it, leaving it vulnerable to wear from handling and cleaning over the centuries. It is for this reason that many surviving examples show only traces of their original gilt schemes — a quality that paradoxically serves as a marker of age and authenticity, since later reproductions tend to present suspiciously pristine gilding.

The finest powder blue and gilt wares display a sophisticated interplay between the mottled ground and the metallic embellishment. Shou characters might be distributed across the body of a tianqiuping (globular vase) in carefully spaced registers, while borders of ruyi-head lappets or lotus scrolls frame the composition. The combination speaks to a distinctly Kangxi aesthetic sensibility: sumptuous yet restrained, technically ambitious yet seemingly effortless.

The decorative vocabulary of powder blue and gilt porcelain is steeped in the language of auspicious wishes. The Shou character, in its many calligraphic variations, expressed the wish for longevity — a virtue prized above nearly all others in the Confucian value system. When rendered within rounded medallions, it invoked the form of coins or bronze mirrors, objects themselves laden with protective symbolism. Such wares were often commissioned as birthday gifts for elderly members of the imperial household or senior court officials, occasions at which the imagery of long life carried particular poignancy.

The powder blue ground itself held symbolic resonance. Blue, associated with the heavens and the element of wood in the Five Elements system, suggested renewal and celestial blessing. Combined with gold — the colour of imperial authority and material prosperity — the palette communicated both spiritual aspiration and worldly success.

For collectors, powder blue and gilt wares present both opportunities and challenges. The mottled quality of the ground glaze is the first point of examination: genuine Kangxi powder blue should display a fine, consistent stippling when viewed under magnification, distinct from the smoother appearance of sacrificial blue (jilan) or the painted blue-and-white technique. The cobalt particles should appear visible as individual specks within the glaze matrix.

The condition of the gilding, while rarely pristine, offers important diagnostic clues. Authentic Kangxi gilt will typically show wear patterns consistent with centuries of careful handling — worn at the highest points of the relief while surviving in protected recesses. The gilt itself, when present, should exhibit a warm, slightly matte tonality quite different from the brassy sheen of modern gold paint.

Provenance, too, plays a significant role in the assessment of these wares. Powder blue porcelain has been collected in Europe since the early eighteenth century, and distinguished examples bear the marks of great historical collections — from J. Pierpont Morgan to Augustus the Strong of Saxony, whose legendary porcelain cabinet at the Zwinger in Dresden contained numerous powder blue specimens.

Powder blue and gilt porcelain occupies a distinctive position in the canon of Chinese ceramics. It stands at the intersection of technical innovation — the blown-cobalt method was without precedent in the ceramic traditions of any other culture — and the deep symbolic vocabulary that gave Chinese porcelain its meaning beyond mere utility or decoration. Each surviving example, with its characteristic mottled ground and traces of gold, bears witness to an extraordinary moment in the history of the kiln: one in which the potters of Jingdezhen, working under the most discerning imperial patronage China had ever known, achieved effects of lasting subtlety and power.

The Chinese Heritage has offered fine Chinese antiques, including powder blue and gilt porcelain from the Qing Dynasty, since 1978. Visit our gallery at Lucky Plaza, Orchard Road, Singapore.