No colour in Chinese material culture carries the weight of symbolism borne by yellow. Reserved by imperial edict for the exclusive use of the Son of Heaven, this luminous hue — visible in the glazed roof tiles of the Forbidden City, in the Dragon Robes of state ceremony, and in the finest porcelains produced at the Jingdezhen kilns — was the visible manifestation of an authority understood to emanate from Heaven itself. Yellow ground porcelain, therefore, occupies a position at the very apex of the ceramic hierarchy: these were objects made for the ruler alone, and their possession by anyone outside the imperial household was, in principle, forbidden.

The Philosophy of Yellow: Earth, Centre, and Celestial Mandate

The privileged status of yellow is rooted in the ancient Chinese philosophical system of the Five Elements (Wuxing, 五行). Within this cosmology, yellow is associated with the Earth element, which occupies the central position from which the other four elements — wood, fire, metal, and water — emanate. This centrality perfectly embodied the Emperor's role as the axis of the human world, the mediator between Heaven and Earth whose righteous governance maintained the harmony of the cosmos.

The Imperial Court codified this symbolism through strict sumptuary regulations. The shade known as minghuang (明黄), "bright yellow," was reserved exclusively for the Emperor. Members of the imperial household of lesser rank were permitted to use progressively paler or darker variants — apricot yellow for the Empress, golden yellow for the heir apparent — creating a chromatic hierarchy that mirrored the social order itself. By the time of the Qing Dynasty, these regulations had been elaborated into a system of remarkable specificity, governing not merely the colour of porcelain but the precise hue of silk, lacquer, and architectural glaze appropriate to each rank.

The Glaze: Achieving the Imperial Egg-Yolk Yellow

The production of a flawless yellow glaze was among the most technically demanding feats of the Jingdezhen kilns. The colour was achieved through the use of iron oxide as the primary colouring agent, applied as a low-fired overglaze enamel. The porcelain body was first fired at high temperature with its underglaze decoration (if any), then coated with the yellow enamel and refired at a lower temperature in a muffle kiln — a process that required precise control of temperature and atmosphere to produce the desired even, saturated tone.

The finest examples display what period connoisseurs described as an "egg-yolk" quality — rich, warm, and faintly translucent, with a surface that catches the light with a soft, almost waxy lustre. Achieving this consistency across an entire vessel, without the pooling, streaking, or discolouration that could result from even minor variations in temperature, was a testament to the skill of the Jingdezhen potters and the rigorous quality control that imperial commissions demanded. Pieces that failed to meet the required standard were destroyed — a practice documented in the imperial records and confirmed by the discovery of sherd heaps at the kiln sites.

Underglaze Blue Floral Sprays on Yellow Ground

Among the most refined expressions of the yellow ground tradition are dishes that combine the imperial yellow enamel with underglaze blue floral decoration. In this technique, delicate sprays of flowers — typically chrysanthemums, lotus, or composite floral scrolls — were first painted in cobalt blue on the white porcelain body and fired at high temperature. The yellow enamel was then applied around and between the blue designs, and the piece was refired at lower temperature.

The result is an effect of considerable subtlety: the blue designs appear to float within the yellow ground, their cool tonality contrasting with the warmth of the surrounding enamel. The precision required is extraordinary; the yellow must be applied with perfect evenness up to the edges of the blue motifs, without overlapping or leaving white gaps. On the finest examples, the transition between blue and yellow is seamless, creating the impression that the two colours were applied simultaneously rather than in separate firings.

This combination carries its own symbolic resonance. Blue, the colour of Heaven, paired with yellow, the colour of Earth and imperial authority, reiterates the Emperor's role as the link between the celestial and terrestrial realms. The floral motifs — chrysanthemums symbolising autumn and scholarly integrity, lotus representing Buddhist purity, peonies denoting wealth and rank — compound the auspicious message.

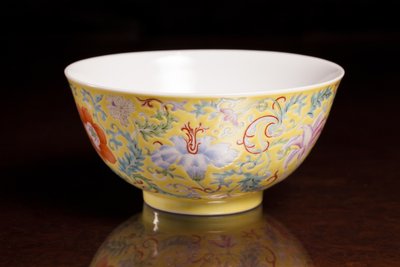

Famille Rose Bowls with Xianfeng Marks

The Xianfeng reign (1851–1861) represents one of the most turbulent periods in Qing Dynasty history. The Taiping Rebellion, which devastated much of southern China, led to the destruction of Jingdezhen by rebel forces in 1853 — an event that effectively halted imperial porcelain production for several years. Wares bearing the Xianfeng mark are consequently among the rarest of all Qing imperial porcelains, and those in the yellow ground famille rose tradition are of exceptional scarcity.

Yellow ground famille rose bowls from this period typically feature polychrome enamel decoration — flowers, fruits, or auspicious symbols — painted over the yellow enamel in the rich palette that had been developed during the preceding Qianlong and Daoguang reigns. The Xianfeng reign mark, rendered in either underglaze blue or iron-red enamel, may appear in either the six-character (Da Qing Xianfeng Nian Zhi) or four-character (Xianfeng Nian Zhi) form.

The rarity of Xianfeng-marked yellow ground wares lends them a documentary as well as aesthetic significance. They are evidence that, even as the empire faced existential crisis, the imperial household maintained its commitment to the production of porcelain of the highest quality — a continuity of tradition that speaks to the profound cultural importance of these objects within the Chinese court.

Collecting Yellow Ground Porcelain

The assessment of imperial yellow ground porcelain begins with the colour itself. The yellow should be warm, even, and possessed of the characteristic "egg-yolk" quality described above. Dull, chalky, or excessively orange yellows may indicate later production or provincial kilns that lacked the refined materials and techniques of the Jingdezhen imperial workshops. Under magnification, the enamel surface should be smooth and free of the bubbling or crawling that can result from overfiring.

The underglaze blue decoration, where present, offers additional diagnostic information. On imperial pieces, the blue should be clear and true, with painting that displays the confident precision of kiln artists working within an established imperial vocabulary. The junction between the blue motifs and the surrounding yellow ground is perhaps the most telling detail: on genuine pieces, this boundary is crisp and clean; on later copies, it frequently shows signs of the yellow enamel overlapping the blue, or of white porcelain showing through at the margins.

Given the strict regulations governing the use of imperial yellow, the provenance of these objects is of particular interest. Many examples that have entered Western collections did so in the aftermath of the looting of the imperial palaces during the upheavals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries — a history that lends these already resonant objects an additional layer of historical weight.