No category of Chinese ceramics has exercised a more profound or enduring influence on the decorative arts worldwide than blue and white porcelain. From its emergence at the Jingdezhen kilns during the Yuan Dynasty to its apotheosis under the Ming and Qing Emperors, the marriage of cobalt pigment and white porcelain body has produced some of the most celebrated objects in the history of material culture. Within this vast tradition, imperial wares from the Yongzheng (1723–1735) and Jiaqing (1796–1820) reigns — distinguished by dragon motifs of exceptional refinement and reign marks of documentary importance — occupy positions of particular distinction.

The Yongzheng Emperor, who ascended the Dragon Throne in 1723, was by temperament a perfectionist — austere, exacting, and possessed of an aesthetic sensibility that favoured refinement over ostentation. Under the supervision of Nian Xiyao, whom the Emperor appointed to oversee the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen in 1726, porcelain production achieved what many scholars regard as the technical and artistic summit of the entire Qing Dynasty.

Yongzheng blue and white is characterised by an extraordinary delicacy of execution. The cobalt pigment, sourced and processed with meticulous care, was applied in thin, precisely controlled washes that produced a blue of unusual softness — less assertive than the brilliant sapphire of the Kangxi period, more luminous than the sometimes greyish blue of later reigns. The painting itself achieved a degree of finesse that reflected the Emperor's personal oversight; period records suggest that Yongzheng reviewed designs submitted from Jingdezhen and returned those that failed to meet his exacting standards.

Dragon motifs on Yongzheng blue and white exemplify this pursuit of perfection. The imperial five-clawed dragon — reserved by sumptuary law for the Emperor's exclusive use — is rendered with a sinuous grace that distinguishes it from both the powerful, somewhat heavy dragons of the Kangxi period and the increasingly stylised versions that would characterise later reigns. Each scale is individually articulated; the whiskers flow with calligraphic precision; the clouds through which the dragon moves are painted with the atmospheric sensitivity of a literati landscape. These are dragons conceived not merely as symbols of imperial power but as exercises in aesthetic excellence.

The Jiaqing Emperor (r. 1796–1820) inherited the throne at a moment of transition. His father, the Qianlong Emperor, had presided over an era of unprecedented imperial splendour, but also one in which the seeds of decline had been sown — corruption within the civil service, population pressures, and the first stirrings of the social unrest that would eventually engulf the dynasty. The Jiaqing Emperor's response was characteristically conservative: a return to established precedent and a reaffirmation of traditional values.

This conservative impulse is legible in the blue and white porcelain of the period. Jiaqing wares consciously emulate the achievements of the Yongzheng and Qianlong reigns, reproducing classic forms and decorative schemes with considerable technical competence. The cobalt blue tends toward a slightly darker, more saturated tone than the Yongzheng ideal, and the painting, while skilful, occasionally reveals a fractional loosening of the exacting discipline that had characterised earlier imperial production.

Dragon motifs on Jiaqing blue and white retain the essential vocabulary of the Yongzheng and Qianlong periods but may display subtle differences in articulation — a slightly fuller body, a marginally less fluid treatment of the mane, a firmer outline to the cloud scrolls — that allow the experienced eye to distinguish them from their predecessors. These are not deficiencies but rather the natural evolution of a decorative tradition as it passes from one generation of kiln painters to the next.

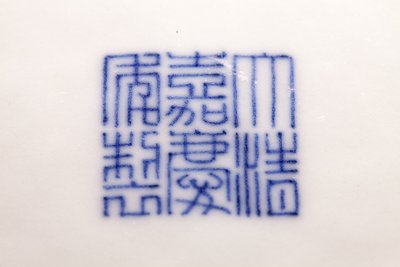

The reign marks on Yongzheng and Jiaqing blue and white porcelain are objects of study in themselves. Chinese reign marks are read in columns, from right to left and top to bottom. A standard six-character mark comprises three elements: the dynasty designation (Da Qing, "Great Qing"), the Emperor's reign name, and the phrase Nian Zhi ("Made during the reign of").

The Yongzheng period saw the consolidation of a significant calligraphic shift. While the Kangxi reign had employed the regular-script kaishu (楷書) form for most reign marks, the Yongzheng potters increasingly adopted the archaic seal-script zhuanshu (篆書), whose more angular, stylised characters lent a quality of classical authority to the mark. This preference was continued and refined during the Jiaqing period.

The subtle differences between genuine period marks and later apocryphal copies — marks applied in homage to earlier reigns rather than as deliberate forgeries — remain one of the central preoccupations of Chinese ceramics scholarship. A genuine Yongzheng mark will typically display a fluency and confidence of brushwork that is difficult to replicate; the characters are balanced, the spacing precise, the overall impression one of unhurried authority.

The dragon, or long (龍), has served as the supreme symbol of imperial Chinese authority since antiquity. On imperial porcelain, the five-clawed dragon was the exclusive prerogative of the Emperor; lesser members of the imperial household were restricted to four-clawed versions, while three-clawed dragons appeared on wares intended for officials and the wider court.

On Qing Dynasty blue and white, the dragon typically appears in one of several canonical configurations. The most common depicts a pair of dragons pursuing a flaming pearl (zhulong ganbu) — a motif that symbolises the pursuit of wisdom, perfection, or the elixir of immortality. Dragons may also appear amid clouds, waves, or amid the formalised wave-and-rock borders (haishuijiangya) that represent the Emperor's dominion over the four seas.

Auspicious designs accompanying the dragon on imperial blue and white include the bajixiang (Eight Buddhist Emblems), lotus scrolls, and the character wan (卍), a Buddhist symbol of eternity. The combination of these elements produces a decorative programme of considerable complexity, in which every motif contributes to a unified statement of imperial legitimacy and cosmic harmony.

The assessment of imperial blue and white porcelain requires attention to the concordance of multiple factors: the quality of the porcelain body, the tone and application of the cobalt pigment, the precision and style of the painting, the character of the reign mark, and the condition and treatment of the foot rim. On genuine imperial pieces, the body should be fine-grained, dense, and exceptionally white. The glaze should be smooth, even, and possessed of a slight bluish tint that is characteristic of Jingdezhen production.

The foot rim — where the glaze terminates and the unglazed biscuit is exposed — is a critical diagnostic area that later copyists frequently fail to replicate convincingly. On Yongzheng and Jiaqing imperial pieces, the foot is typically neatly trimmed, with a rounded or slightly bevelled profile, and the biscuit is smooth and white. The interior of the foot ring may show traces of firing sand or kiln grit consistent with period firing practices.

For the serious collector, direct comparison with published examples in institutional collections — the Palace Museum in Beijing, the National Palace Museum in Taipei, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London — remains the most reliable method of developing the "eye" that distinguishes the connoisseur from the casual enthusiast.

The Chinese Heritage has offered fine Chinese antiques, including imperial blue and white porcelain from the Qing Dynasty, since 1978. Visit our gallery at Lucky Plaza, Orchard Road, Singapore.